Where Do You Put Your Fingers on the Violin?

/Any beginning violinist can tell you what makes violin is so hard—knowing where to put your fingers! While decals like First Frets can help, you can’t put a sticker where every single note exists on the violin. You can memorize where certain notes are on the violin, and your muscle memory might get pretty adept at finding those notes, but if you don’t understand two important concepts, then you will never truly understand where to put your fingers.

These two concepts are essentially the two reasons learning violin is so hard. However, these two concepts are often left out of violin lessons all together. Why would teachers leave out the two things that could help everything make sense? Well these two concepts take a lot of self-study to master. They also require in-depth study. You can’t understand these concepts with just a few words of advice from your teacher every week. When you only have 30 minutes to talk about songs, tone production, rhythm, note reading, posture, and so on, there’s hardly time to focus on these concepts.

But if you don’t learn these concepts, it’s the same as just learning certain phrases in another language as opposed to really understanding how the language works. You may be able to play songs and read challenging music, but without understanding these two things, you will never truly understand the language of the violin. These two concepts are not dry by any means, but they can be hard to grasp. But I’m going to help you with that!

Are you ready to learn the real language of the violin? Are you ready to know what two secrets could help everything make sense? Here they are: ear training and music theory.

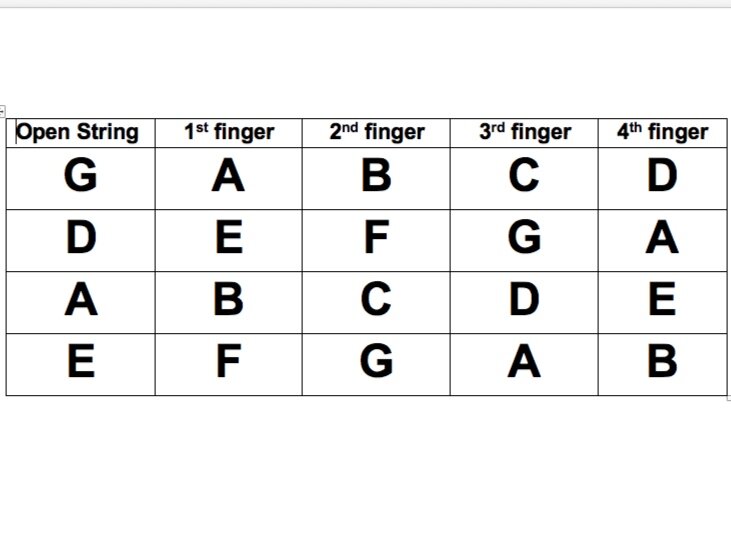

Before I explain why these two concepts are so important, let’s take a moment and talk about where to put your fingers in first position. The violin strings are (starting from the lowest string) G, D, A, and E. Your left hand fingers are numbered 1-4. Index finger being 1st finger, middle finger is 2nd finger, ring finger is 3rd, and pinky is 4th finger. (Remember that the musical alphabet goes from A-G. After G, your next note is A but a higher A than the first A you played).

Okay, notice how there are three letters separating each string?

G (A B C)

D (E F G)

A (B C D)

E

Those notes in parentheses are going to be your 1st, 2nd, and 3rd fingers respectively. What about 4th finger? Well it’s the same note as your open string below it.

When you are first learning, you will learn a finger pattern in which the 2nd and 3rd fingers are touching on every string (half steps apart) and all the other notes will be whole steps apart.

Just knowing what note you are playing won’t necessarily help you know where to put it on the fingerboard. Sometimes your fingers will be right next to each other, sometimes they will be a step apart. You have to understand how each note relates to the note before it in order to know where the finger goes. You have to be able to hear how the next note sounds. Which brings me back to those two big concepts.

What are these concepts?

Ear Training

Ear training is a term we use to describe the process of teaching our ears to to discern certain things in music. You might have heard of people with perfect pitch—people who have the ability to say what a note is just by hearing it. (You don’t have to have this ability. I definitely don’t! But you can get close). Or you may have heard of “playing songs by ear”—without looking at music. These are both ear training skills, but ear training is more complicated than just that. Ear training involves the ability to hear and understand the distances between notes, the quality of chords, whether a song moves by step or by skips, and most importantly for the violin, whether or not a note is in tune!

Since there are no frets or keys on the violin fingerboard, you have to be able to hear a note in your head before you play it in order to know if it’s in tune once you put your finger down. This sounds complicated, but with practice it can become second nature.

Before we talk about how to start tackling ear training, let’s discuss that second big concept: music theory.

Music Theory

Music theory is the the structure behind songs. It’s like the frame of a house. You don’t always see it or understand it, but without it, music would be a big mess. Theory involves understanding how all the notes work together.

For instance, when students first learn violin, they often learn “high 2” or high second finger. Teachers rarely take time to explain why the 2nd finger is high because it would take too long. “Just make sure you call it F sharp on the D string and not F. Don’t worry about why it’s sharp right now. Oh and yes, the 2nd finger on the A string and E string are also called sharps, but not the second finger on the G string. It’s just B natural, but you don’t have to say natural. Just call it B.”

Confused yet? Just wait until you start learning to lower that 2nd finger and play “low 2.” “Now that 2nd finger on the A string is no longer sharp, it’s C natural, but you’re still going to need to play “high 2” on the D string and G string those are still sharp, well except for the G string. That one’s still just B natural. Don’t worry about why it switches around, we’ll tell you later!”

If you don’t understand the framework behind music, you will just be trying to memorize worthless rules to put your fingers in the right place. But those “rules” will only apply when you are in first position. (The collection of notes that you learn first. Eventually you will learn higher positions and move up the fingerboard.) With a little music theory knowledge, you’ll know why some of those notes are sharp, which ones are sharp, when they’re not sharp, and how to play those notes all the way up the fingerboard and not just right there in first position.

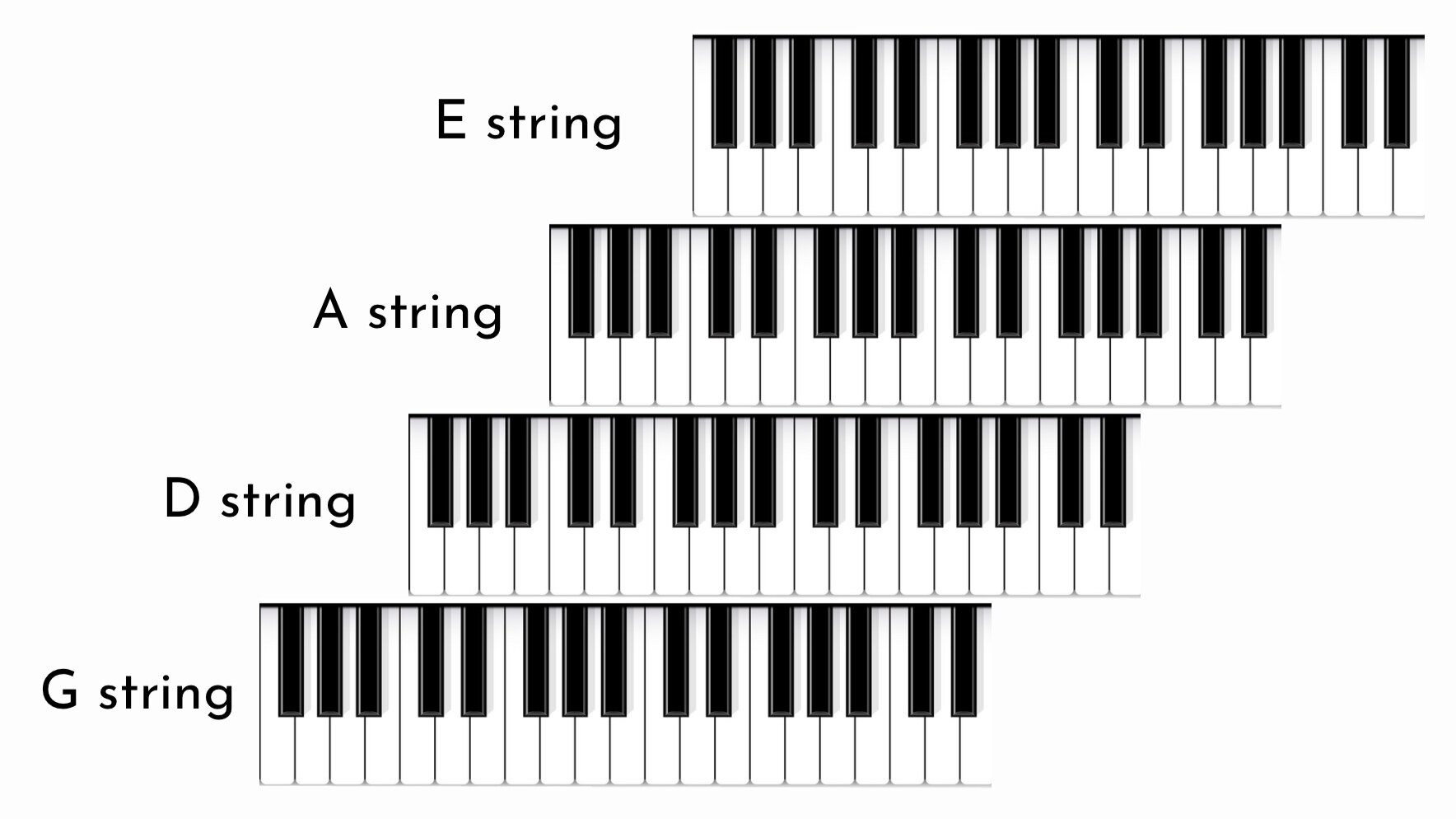

If you look at a piano key board, you can see all the notes and their relationships to each other. Each violin string works the same as a keyboard, except you can only see the notes in your head! And there are 4 strings, each string starting with a different note, so really something like THIS is what you should be seeing in your head (this isn’t an exact representation of the notes on each string. It just gives you an idea of how each string is like a keyboard).

If it looks confusing, don’t let that deter you. With just a little bit of theory, you will be able to build this structure in your head when you play.

So how do you start learning the language of the violin? Check out my easy ear training exercises to get started teaching your ear to be the boss! As you learn about ear training, you’ll see how it’s intertwined with music theory. Check out my music theory lessons to start learning how to see the structure behind music.

Learning ear training and music theory might seem like big tasks, but gaining even a basic understanding of these concepts will not only make playing the violin easier, it will make it more enjoyable! You will not only be able to understand the language of music when other’s play, you will be able to speak the language and make your own music! How wonderful is that?

Happy (ear training, music theory) Practicing!